Community - Los Angeles

Life Beneath Hollywood’s ‘Bamboo Ceiling’

Laura Wong with one of the costumes from “Seppuku,” a short film she costume-designed in 2016. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

Since June 2020, we’ve asked for your stories about how race and ethnicity shape your life and and published as many of these stories as we can. We call this year-long effort Race in LA. Click here for more information and details on how to participate.

By Laura Wong

I work in the film industry, in costumes.

I remember sitting in a meeting a few years ago, casting extras for a major feature film. We were going down the list of scenes, all very routine, discussing what type of people should be in the background for each one: A 50-50 male-female split at the café — no problem. Older crowd at the charity benefit, fine.

Then we made it to a scene in a fictional paralegal’s office, and someone said “This would be a really great spot for an Asian.” The whole room erupted in a murmur of agreement.

“SUCH a great idea!” I heard.

“Yes, what a great chance to add some diversity,” someone else said.

It was routine, nothing egregious about it, just everyday stuff. No one said anything. No one even noticed.

Except me, the only person of color in the room.

MY LA ROOTS (AND WHY THEY MATTER)

I am a mixed fourth-generation Chinese American, with L.A. roots more than a century deep.

My mother’s side is a mix of German and British. On my father’s side, my great-grandfather Don Sue Wong arrived in Los Angeles in 1908. He was brought over on a merchant visa to work at the Kwong On Company in old Chinatown.

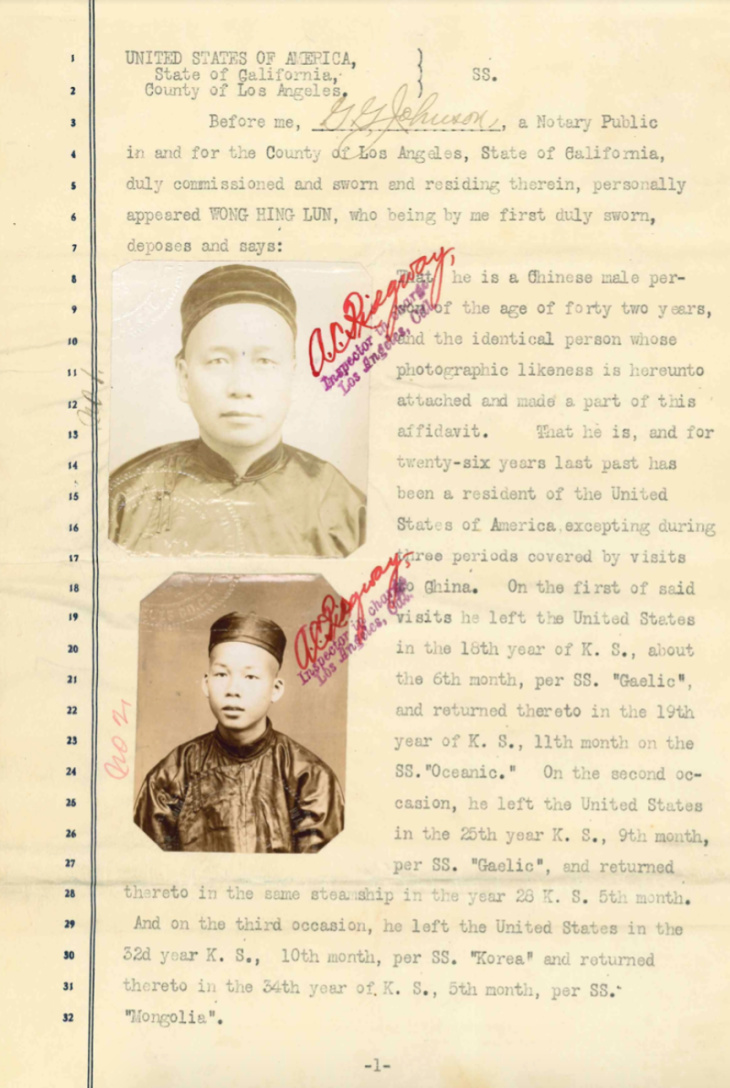

An immigration document for Laura’s great-grandfather Don Sue Wong (bottom photo) from 1908. Hing Lun Wong (top photo) may or may not have been his father. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

It was located right about where the onramp to the 101 Freeway currently is, across from the plaza at Olvera Street.

According to the immigration documents we have, he arrived by boat all the way from “Ping Lok village, Sun Ning district” which is an area in the Pearl River Delta now known as Taishan, in Guangdong province in southern China.

We will never know for sure, but there is a chance he may have been a “paper son” of Hing Lun Wong, the man listed on his documents as his father. This was during Chinese Exclusion, and after the Hall of Records in San Francisco was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire, many hopeful Chinese immigrants were able to come to the United States by posing as relatives of U.S. citizens. It was a loophole that allowed them to circumvent laws that were meant to keep them out.

Don Sue Wong later brought his wife here from China, and they had five children, Andy, Anna, Ruth, Hazel, and my grandfather, Wayne.

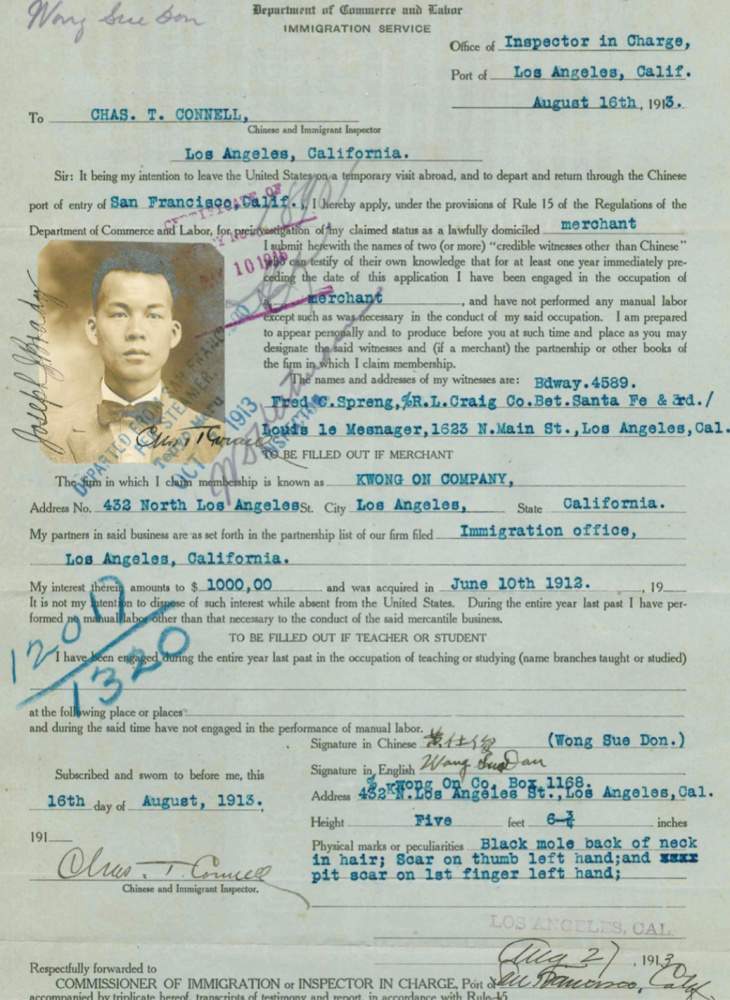

Despite the hardships of discrimination and poverty, the family managed to make a life for themselves, growing vegetables on farmland they leased in Indio. They leased because Chinese were not allowed to own property at that time. They also ran a produce market in L.A.

An application by Don Sue Wong, Laura’s great-grandfather, to travel to China and return back to the U.S. in 1913. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

Don spent most of his time working on the farm, while the family made extra money in L.A. by de-stemming strawberries and un-shelling walnuts for pennies on the dollar. During the Great Depression, they burned the walnut shells at home for heat. It was a hard life, but they managed to scrape by.

In the 1950s, the family was finally able to purchase a grocery store on Beaudry Avenue near downtown L.A., where the entire family worked.

Wayne, my grandfather, served in World War II, deploying to the Pacific just before the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima. He served in the Philippines, and then in Japan during the Occupation, repairing phone lines.

We recently uncovered rolls and rolls of negatives of black and white photographs he shot during his time there, as well as the camera he shot them with.

You have to wonder what that experience was like, serving in the U.S. Army as an Asian American at that time, in a primarily white occupying force. One of my favorite photos is of a young Japanese girl looking up at my grandfather with a curious look on her face.

A photo of Wayne Wong, Laura’s grandfather, while serving in the U.S. Army in Occupation-era Kyoto, Japan, 1945-1946. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

After he returned from service, he went to Hong Kong to visit a family friend, and there he met and married my grandmother, Dolly Chan.

The rumor in the family is that Dolly’s father had originally come to America during the Gold Rush era and worked building the railroads. He took the money he saved from that time and went back to Hong Kong, where he was able to start a very successful chain of wholesale grocery stores both in Hong Kong and in the Philippines.

When the Japanese invaded Hong Kong, my grandmother Dolly was sent to the Philippines, where her parents thought she would be safer. As the war progressed, the situation became increasingly dire. Some of her more vivid memories were of having to shave her hair and dress like a boy, and hiding in the attic to avoid being captured by the Japanese. Her father was killed in the war, but she managed to survive and eventually moved back to Hong Kong, where she met my grandfather.

When my grandmother arrived in the U.S. she gave the immigration official her Chinese name, but the official couldn’t pronounce it. He said, as my grandmother recalled, “You’ll need an American name, so since you look like a China doll, I’ll name you Dolly.”

Dolly Wong, Laura’s grandmother, in the 1950s with her children, (from l. to r.) Marie, Diane, and Curtis. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

My father and his two siblings, Marie and Diane, grew up in Silver Lake, in the house I now call home. I remember hearing various stories over the years about his growing up in this house. About raising chickens in the yard, and his pet hamster named Elmer Fudd. Squeezing through the gate to sneak in and play on the playground at Micheltorena Elementary.

And a few not-so-fond memories, like the time he took his home-built telescope out to the back of the house to look at at the sky, and one of the neighbors called the LAPD, thinking the telescope was some sort of weapon. He ended up held at gunpoint in his own driveway by the police, until he was able to convince them that there had been a misunderstanding.

Laura’s father Curtis, left, and his two sisters as children in Los Angeles, 1960s. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

As my father grew up, he went to Marshall High, followed by UCLA and then Cal State L.A. for his MBA, eventually moving to Seattle to pursue a career in tech.

I was born in L.A. and moved up to Seattle when I was six years old. I lived there through high school, and then moved back down to L.A. for college and never left.

Although I grew up hearing my grandparents speaking Cantonese, I never learned to speak it myself. My dad knew it as a kid, but claims he has forgotten it all, although I think he understands more than he lets on.

Most of my cultural memories growing up are around food. We would go out for dim sum on weekends with the family, and I would feel completely at home choosing between the array of food in bamboo steamers cruising along on shiny metal carts. Dolly, my Chinese grandmother, would constantly top off my plate with more food, saying “too skinny!”

I’m extremely proud of my family and our long history in this country. But even in the bustle of Chinatown, amongst family, I never really felt “Chinese” enough. Being mixed, and with my lack of knowledge of the language, it always felt like true belonging was something a little too distant for me to grasp.

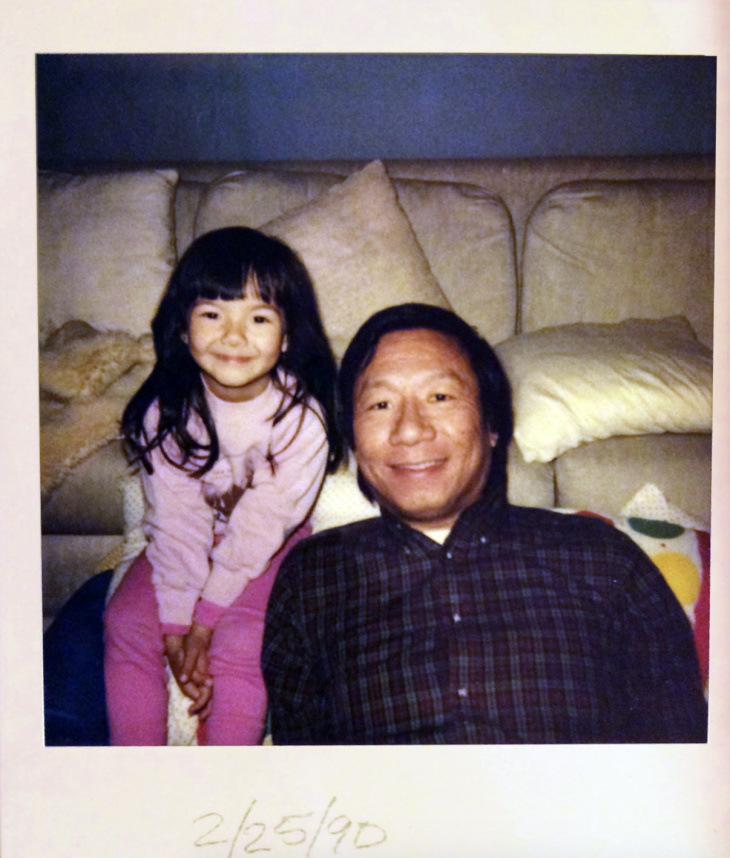

Laura and her dad, Curtis, in 1990. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

So much of the narrative of Asian Americans in this country is focused on the more recent immigrant experience, and after four generations of my family here, sometimes I feel like a bit of an outlier.

Many of the things that newer generations of Asian Americans grow up with were not necessarily the same things I experienced. We ate Chinese food at home, but a lot of it was American-Chinese hybrid foods: In our family, we eat sticky rice stuffing at Thanksgiving with our turkey.

My dad didn’t pressure me to go to school to be a doctor or a lawyer. In fact, he was completely encouraging when I decided to go into the arts.

A SEAT AT THE TABLE — BUT NO VOICE

And so here I was, many years later, a working costumer in a Hollywood meeting room, quietly raging inside.

I guess in a film with a cast that is more than 90% white, it’s considered progressive to have a silent Asian American woman in the background, playing a paralegal.

I just sat there, feeling invisible. Like a piece of set dressing. Like that paralegal, sprinkled in for some “flavor.”

Most of the time, I do feel invisible in my industry. I don’t see people who look like me reflected on-screen. When I do, even if there are Asian faces on the screen, I know that more often than not, the people behind the scenes creating these worlds are not people of color.

People say, “Be glad you have a seat at the table,” but what good is a seat if you have no voice? By being a part of this system, I feel complicit in my own erasure.

For the most part, racism in our city isn’t in the form of burning crosses or police with guns. It’s in the day-to-day exhaustion of dealing with microaggressions and particularly in Los Angeles, in having to navigate well-intentioned white liberals.

There’s this stereotype of “Hollywood liberals” and to an extent, it is true. But just because someone identifies as liberal or progressive doesn’t mean that they aren’t perpetuating white supremacy, or that they are aware of how they do it.

In fact, some of these well-intentioned people prove to be the most difficult to deal with in many cases, because none of them believe that they are part of the problem.

“I voted for Obama,” they say.

“I love sushi and tacos,” they tell me.

Most of the things I deal with at work are not anything someone would file a complaint with human resources over, and can honestly be trivial compared to the things my Black and Brown coworkers face. But nonetheless, each time these things happen, it stings.

Laura and fellow costume designer Sueko Oshimoto with costumes they worked on from “Westworld” Season 2’s “Shogun World,” during a 2018 exhibit at the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

There are the offhand remarks made by often clueless people. I was once introduced to a white male coworker when he walked over to me and another colleague (who happened to be an Asian female as well) and announced loudly “Well, you must be tech support!”

In another job, I worked with a costumer who would repeatedly rant about China and their “crappy workmanship,” then when I was in the room would turn to me and say, “No offense.”

Other times, it feels like I’m there to provide validation to those around me. One white female designer I worked with came to me specifically to announce that for one scene, she had decided to make some of the background actors people of color — although the film had zero speaking parts for people of color.

“Isn’t that a great idea?” she asked, her tone making it clear that she was seeking some sort of “woke” stamp of approval. It made me uncomfortable. Is this the progress we are looking for? Being visible but silent in the background, while white people get to speak?

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- Boricua At Home, Black In The World: An Afro Latina in LA

- As A Black Nurse At The Pandemic’s Frontlines, I’ve Had A Close Look At America’s Racial Divisions

- ‘What Are You?’ ‘Are You Adopted?’ A Biracial Black Woman Gets Real About The Questions People Have The Nerve To Ask

- Reading While Black, And Other Ways To Court Trouble

- Reparations And Reinvestment: Contemplating The Proverbial ’40 Acres And A Mule’ Today

- Claiming My Dignity On A San Fernando Valley Street

- The Day My Brother Learned To Fly

- In The Process Of Becoming American: A Proud Son Of Immigrants Reflects On His Family’s Past And Future

- ‘Black Enough?’ Mixed Musings On My Skin Color, Hair, and Heritage

- Please Do Not Call Me A ‘Mutt’ (Not Even You, Mom)

- Connecting Family Stories: A Latina Angeleña Explores Her Deep California Roots

- From ‘Go Back To Your Country’ To A Vice President-Elect Who Shares My Grandmother’s Name

- How To Participate In Our Series

Sometimes it feels like we are seen as “all the same,” such as when a designer asked a Korean colleague of mine questions like “What does the dragon symbolize in Chinese culture?” We joked about it afterwards (“I don’t know, lady, I’M KOREAN”), but it was still uncomfortable.

There are also instances where it is clear to me that I am seen as “Asian Woman,” instead of as an individual. On one job, our basecamp where the trailers were parked was set up in the parking lot of a Korean church. I remember trying to pull into the lot only to be stopped by a security guard who kept saying “NO CHURCH TODAY!” It was only after I demonstrated proof that I was a part of the crew, and not the congregation, that he let me in.

The Hollywood glamour of a muddy basecamp full of trailers, Downtown L.A. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

Or the time a Teamster cornered me in a parking lot to insist that we had worked on a show together years ago. Turns out he had me confused with another Asian person.

Then there are the more overt instances, such as when an outside vendor I work with asked the classic “Where are you from?” that all mixed people are familiar with. I responded “I’m from here.”

“No no, but where are you REALLY from?” he countered. I maintained, “I’m from the U.S.”

“Okay, but where are your parents from?” he persisted. “They are also from here,” I replied, knowing exactly where he was going with this.

“But you’re not a REAL American” he said, gesturing at my face. Apparently, to be a real American you need to be white.

It’s particularly rich, considering my family has been here for nearly a century and a half, to be told that I’m not American enough by people whose families may well have arrived in this country long after my own ancestors did.

I once worked with another Asian costumer who told me that he doesn’t use his real name at work because “white people can’t pronounce it”.

In an industry that tells you that you have to “have a thick skin,” where does the line fall between being tough and enabling your own oppression?

‘A GREAT SPOT FOR AN ASIAN’

This last summer, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police, I found many of my industry colleagues being willing to have much more candid conversations than ever before about their experiences with racism in the film industry.

Within the unions I belong to, diversity committees were formed, and designers and costumers were having open conversations about their experiences. It was like a dam had opened up, and suddenly people felt like they could share things that they had been conditioned to keep quiet about for so long.

The many colors of fabric: A day on the job for a costume designer, inside a DTLA fabric store. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

Some consistent threads in these conversations were about representation, and a lack of upward mobility for people of color. Consistently, those who book the biggest jobs and win the most prestigious awards are white. While there are exceptions (who wasn’t thrilled to see Ruth E. Carter win the Oscar for Best Costume Design for “Black Panther”?) they are certainly not the norm.

A common complaint I heard from my Black colleagues is that they are pigeonholed to only doing “Black shows.” I thought about that a lot, and realized that I wouldn’t be able to pigeonhole myself into only doing “Asian shows” if I wanted to, mostly because those shows don’t seem to exist.

Why is that? I know from my own family history that there are rich, fascinating stories to be told about the Asian American community, so why is it so rare to see those stories on screen?

I decided to channel my frustration with this feeling of invisibility and lack of representation into some research. Since I work in costumes, I chose to focus on costumes. I made a list of every film or TV project from the last 20 years I could find that met one of the following criteria: leading principal Asian cast; Asian-related subject matter; an Asian-related setting.

For each project that made it onto my list, I went through and researched who designed the costumes, the budget of the film, and where it was shot.

I came up with 63 “Asian” projects. Of those, only 13 had a costume designer of Asian descent.

Of those, just three projects had a budget of over $3 million: “Slumdog Millionaire” designed by Suttirat Larlarb, and “The Namesake” and “Life of Pi” which were designed by Arjun Bhasin. All three of these were shot entirely or partially outside of the United States.

The remaining 10 projects I could find that had an Asian costume designer were in the ultra-low-budget independent realm. All of the big budget film projects (over $100 million) on my list were designed by white or white-passing costume designers.

Now, I would love for someone to prove me wrong about any of this, because these results were incredibly depressing. How are you supposed to believe you have a future in a field where it’s so clear that you will never be allowed to have agency in your own representation?

You can bring on “cultural advisors” all you want, but if ultimately the people in charge of the final decision are all white, is that really representation?

The “bamboo ceiling” has been written about extensively in other fields. It refers to the fact that Asian Americans are statistically the least likely to be promoted to positions of leadership, despite having higher than average educational achievement. Why is this?

There are the stereotypes, of course. That we’re quiet, that we lack leadership skills, that we’re weak and self-effacing. These are all the tropes I’ve heard about why Asian Americans don’t succeed in leadership, especially Asian American women. But the thing is, it’s not just Asian Americans, its people of color across the board.

Every year, UCLA compiles the “Hollywood Diversity Report” which brings to light a simple fact: the overwhelming majority of those in charge of decision-making in film and TV are white and male. Progress has been made, of course, but more so in front of the camera than behind it.

In an industry that purports to be so progressive, why is there so little upward mobility behind the scenes for people of color? I’ve heard all sorts of explanations, which tend to follow these same lines of thinking:

- People tend to hire who they know. The majority of the people who work in film are white. They know white people. So, they hire white people.

- People also like to hire people with “experience.” Who has experience? Those who have been given opportunities in the past. Who has been given opportunities in the past? White people.

I can say that in my own career, I’ve worked for a costume designer of color only once.

Laura with costumes she worked on from “The House with the Clock in its Walls” at a 2018 FIDM exhibit in Downtown L.A. (Courtesy of Laura Wong)

It also doesn’t help that the entire system is built to reward those with existing wealth and privilege. It is often expected that people work as a PA (production assistant) at first to “learn the ropes,” in a non-union job with minimum wage and no benefits.

How do you afford to work as a PA in a high cost-of-living city like Los Angeles without having an existing system of financial security? Especially when there is no guarantee that you will ever be able to join a union, except by chance? I know people who had to PA for 8 to 10 years before they were given an opportunity to join. How many otherwise talented people, with limited means, gave up?

Honestly, I can’t blame them. Because here I am, having gone through all of those hoops and jumped all of those hurdles myself, and while I should be feeling great about having been lucky enough to make it this far, I’m still plagued by this guilt of feeling complicit in my own erasure.

How do you keep your soul in an industry where you barely exist? How do you fix a system so much larger than yourself? Sometimes it’s hard to have faith that change will happen.

But if anything gives me hope, it is the conversations I’ve had and connections I’ve made with fellow BIPOC people in my industry over the last year. There is so much value to be had in community and the validation of shared experience, and it makes such a difference to know you’re not alone.

It really feels like a dam has broken and people are tired of staying quiet.

I’ve been asking myself, what would I say in that extras casting meeting if it were to happen today? Would I say something this time?

I’ll tell you what I think a “great spot for an Asian” would be: in charge.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Laura Wong is a Los Angeles-based costume designer and costumer who works in theater, film, and television. Laura specializes in Japanese costume and textiles, and has studied the subject extensively in Japan and in the United States.

She recently completed her certification in 2018 as a licensed kimono dresser and sensei with the Southern California branch of the Yamano School, which is based in Tokyo. In addition to her film work, Laura owns her own business, Boro Boro, where she sells vintage Japanese textiles and kimono. With her free time, she is a big foodie and loves to travel.

All copyrights for this article are reserved to LAist